The advent of the Internet has reshaped many areas of life, including the practice of medicine. As the virtual realm has grown, the traditional in-person encounter between healthcare provider and patient has become supplemented by telemedicine (TM), in which providers connect electronically with patients for such purposes as health screening, specialty consultation, and diagnosis and treatment of disease.

Telemedicine is one aspect of the broader practice of telehealth (TH), which encompasses a range of clinical services, including patient monitoring, counseling and education, as well as adminis- trative functions delivered via patient portals, text messaging and email. The scope of telehealth capabilities has expanded dramatically in recent years due to a proliferation of technological innovations, including wearable and implantable devices, new software applications and interconnected health platforms. (See “Forms of Telehealth”)

By 2017, 76 percent of U.S. hospitals engaged with patients through wireless communications and Internet-based systems, compared with just 35 percent in 2010. Already on an upward trajectory, virtual care has recently surged due to the COVID-19 pandemic and consequent restrictions on in-person clinical encounters. According to one source, providers reported seeing 50 to 175 times more patients via telehealth after the pandemic struck than before its onset. It is not yet clear if this remarkable expansion in remote care signals a permanent shift in healthcare delivery, as some caution in regard to TM/TH has been expressed recently at the federal level. However, considering the convenience and efficiency of TM/TH services, and the general trend toward connecting digitally with patients, these technologies will probably continue to flourish even after the pandemic wanes.

Forms of Telehealth

Telehealth – also known as telemedicine, digital health, e-health and virtual care – refers to healthcare services delivered remotely using advanced electronic technology. Some of the more common telehealth modalities are described below:

Video conferencing

Live two-way interaction between patient and healthcare provider using audiovisual telecommunications technology.

- Real-time healthcare services and consultations for remote patients.

- Annual wellness visits to clinics and medical offices.

- Collaborative consultation, medical diagnosis and treatment by physicians and other providers based in different locations.

- Convenient referrals to physically distant specialty providers.

- Emergency and critical care in outlying locations, including prompt assessment of patients and consultation with specialists.

- Mental health services for rural-based or underserved patients.

Store-and-forward or asynchronous video

Electronic transmission of patient health and medical data to a healthcare provider, who then treats the patient at a later time.

- X-rays, MRIs, photos and other images used for diagnostic purposes by primary or specialty providers.

- Prerecorded video clips of patient examinations used to enhance the diagnostic process.

- Patient data – including electronic health records, laboratory reports and medication management files – transmitted to specialists for use in consultations.

- Translated healthcare records of non-English-speaking patients to facilitate provider treatment or consultation.

Monitoring and diagnostics

Electronic collection of patient data via “wearables” and “implantables,” in order to enhance clinical monitoring and treatment of conditions.

- Physiological data – including blood pressure, heart rate, weight, and levels of oxygenation and blood sugar, among other metrics – gathered in real time.

- Comprehensive reports on chronic diseases – e.g., diabetes, hypertension, asthma – used for data-driven decision-making and virtual patient education.

- Device-initiated alerts to providers regarding patient noncompliance with diet recommendations, activity directives and other aspects of the treatment/care plan.

Mobile health or “mHealth”

A subset of telehealth that – using software applications designed for smartphones and other handheld communication devices – focuses on educating patients as well as connecting them electronically with their providers.

- Personalized educational applications that promote patient selfmanagement of medical conditions, such as asthma and diabetes.

- Tools that integrate with electronic health records and offer providers a more detailed view of a patient’s medical history.

- Interfaces with wearable tech devices that facilitate real-time review of patient data by members of the healthcare team.

- Automated reminders to change surgical dressings, take medications or otherwise follow post-procedure recovery instructions.

GAO Raises Questions About Efficacy, Efficiency of TM/TH

In May 2021, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) testified to Congress that more research is needed before the decision is made to permanently expand telemedicine and tele- health (TM/TH) coverage for Medicare and Medicaid recipients.

Acknowledging that, for safety reasons, remote visits were essential during the pandemic, the GAO expressed uncertainty as to the effects of electronic encounters on quality of patient care. In addition, the GAO observed that greater utilization of TM/TH capabilities could increase program expenses, as some safeguards have been suspended during the COVID-19 emergency. Noted one GAO official, “Careful monitoring and oversight is warranted to prevent potential fraud, waste and abuse.”

The GAO testimony was in response to bills introduced in both the House and Senate to retain certain TH-related flexibilities for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries – including elimination of originating site requirements – that were implemented when COVID-19 struck in the spring of 2020. In the absence of new legislation, these rule relaxations are scheduled to expire when the pandemic ends.

The debate at the federal level indicates just how rapidly virtual care is evolving. As the coronavirus crisis ebbs and flows, healthcare leaders need to reassess all aspects of TM/TH on an ongoing basis and remain alert to shifts in the legal, regulatory and payer environment.

Sources: King, R. “New House, Senate Bills Aim to Make Telehealth Expansion Permanent in Medicare, Medicaid.” Fierce Healthcare, May 25, 2021. Mitchell, H. “GAO Tells Congress to Halt Expanding Telehealth Until There’s More Research.” Becker’s Hospital Review, May 20, 2021.

As with any major change in medical practice, potential ramifications of telemedicine include an array of associated liability exposures. In an age of swiftly evolving and maturing TM/TH capabilities, all types of healthcare organizations should consider reviewing and enhancing their risk management programs with respect to remote care. This edition of Vantage Point® focuses on five key areas of concern:

- Rapidly changing regulations and related compliance issues.

- Provider licensure laws and ongoing reform efforts.

- Delegation requirements and documentation standards for licensed, non-physician providers, including physician assistants and advanced practice nurses, who deliver a significant amount of virtual care in some settings.

- HIPAA exposures connected to use of digital platforms.

- Vendor assessment and due diligence.

In addition, a checklist of documentation safeguards is included on pages 8-12 to aid providers and organizations in creating a clear and defensible record of virtual care and demonstrating compliance with regulatory parameters.

Maintain an agile, responsive regulatory compliance program.

Legal obstacles restricting the use of TM/TH services have been relaxed during the pandemic, in order to enhance safety and increase patient access to healthcare providers and organizations straining to meet the unprecedented demand for their services. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act – which permitted delivery of remote services to a wider range of patients, regardless of their location and underlying condition – was enacted by Congress in March 2020. In addition, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) modified existing regu- lations to make it simpler for providers to offer virtual care services outside of previously designated rural areas, across state lines, and to both new and established patients.

Financial and technological factors also have contributed to the movement toward virtual care. Health insurers have increased reimbursement for remote services, while online platforms for virtual care have expanded to include Zoom, Skype and FaceTime, among other popular and user-friendly options.

The situation is fluid, and the easing of TM/TH-related regulations and other changes may not continue post-pandemic. As federal and state agencies begin to establish a longer- term legal framework, healthcare organizations should be on the alert for the issuance of further directives and updates relating to telemedicine. The following measures can help strengthen compliance during this time of rapid change:

Create a chronological inventory of regulatory changes. The compliance program’s files should be well-organized, providing easy access to important dates, such as exactly when notice was received of new directives and when this information was conveyed to providers and staff. The filing system should also be user-friendly, permitting easy dissemination of directives to staff and providers via training forums, email, text messaging and institutional websites.

Digitally document compliance activities. In the event of a regulatory action, state and local surveyors will request a compre-hensive record of compliance efforts. An electronic repository of telemedicine-related protocols, updates, communications and other actions can help strengthen defensibility against potential claims. The following compliance efforts, among others, should be documented:

- Adoption or revision of policies and procedures in response to legal/regulatory actions.

- Training of providers and staff on the scope and timeline of virtual care initiatives.

- Administrative review of policies involving areas of high risk exposure, including provider licensing and credentialing, patient privacy and confidentiality, and claim submission for virtual care services.

Remain abreast of provider licensure requirements.

After decades of discussion about the possibility of easing virtual care restrictions, TM/TH licensure laws and regulations remain primarily within the purview of individual states. At the height of the pandemic crisis, CMS temporarily waived the in-state licensure requirement for Medicare and Medicaid patients. Soon afterward, a number of states lifted similar restrictions in order to facilitate interstate practice. However, the vast majority of states continue to require that physicians and other providers who engage in virtual care be licensed in the state where the patient is located.

Given the legislative volatility regarding interstate licensure, it is imperative that hospitals and other healthcare organizations review current licensing requirements in their jurisdiction when verifying a provider’s authorization to legally practice TM/TH. (For a state-by- state listing of licensure standards and policy statements, visit the Federation of State Medical Boards.) In addition, organizational leadership should remain cognizant of the following interstate reform measures designed to facilitate remote practice:

- Interstate licensure compacts, which build upon the current state-based medical licensing system by permitting providers to obtain an out-of-state license from participating state members.

- License reciprocity, under which certain states mutually honor one another’s provider licenses. (Note that some states issued reciprocity declarations as a means of suspending in-state licen- sure requirements during the pandemic crisis.)

- Telehealth-specific licenses, whereby states grant temporary licensure to provide needed services remotely across state lines. These temporary provisions typically include certain restrictions for providers, such as agreeing not to open a physical office in the authorizing state.

Is State-based Provider Licensing a Major Roadblock to Virtual Care?

The temporary easing of licensure requirements due to the pandemic has renewed the debate over interstate licensing of remote care providers. Some critics believe that our current state-based approach to licensing is obsolete and should be updated to enable wider use of telemedicine, thus increasing efficiency, convenience and patient access to care.

The discussion of regulatory alternatives continues. One proposal involves issuing a federal license to providers who prac- tice telemedicine across state lines, in addition to their active state license. While the idea has garnered some degree of popular support, others view it as undermining the disciplinary function of state-based licensure systems.

For more information about licensing reform issues and efforts, see Svorny, S. “Liberating Telemedicine: Options to Eliminate the State Licensing Roadblock.” Cato Institute, November 15, 2017.

Clarify the basic parameters of remote care delivery.

It is essential to delineate the parameters of virtual care delivery and to communicate these protocols to applicable practitioners. While the following suggestions generally apply to any providers authorized to deliver TM/TH care, they are particularly relevant to advanced practice providers, especially in terms of licensing, scope of practice, documentation and supervision:

Approved providers. Know what types of providers are permitted to engage in virtual care. Depending upon jurisdiction, authorized telehealth providers may include not only physicians, but also nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, physician assistants, and licensed counselors and therapists. The following resources explore the issue of who is approved to provide TM/TH care:

- APRN Compact Legislation, a proposal that, if enacted, would institute a multistate license permitting advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) to practice in all compact states.

- Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB), which provides current information on licensing and regulatory requirements and State Executive Emergency Orders.

- Garber, K. and Chike-Harris, K. “Nurse Practitioners and Virtual Care: A 50-State Review of APRN Telehealth Law and Policy.” Telehealth and Medicine Today, June 2019.

- The Psychology Interjurisdictional Compact (PSYPACT), which authorizes eligible psychologists to practice telepsychology across member state lines.

- State Telehealth Laws and Reimbursement Policies, a report issued by the Center for Connected Health Policy, a program of the Public Health Institute, April 2021.

- Telehealth Licensing Requirements and Interstate Compacts, a compendium included on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services telehealth website.

Licensing. Verify the provider’s authority to deliver virtual care with the relevant governing body, such as the licensing board for nurse practitioners, social workers, or therapists and psychologists.

Scope of practice. Delineate prescribing parameters for advanced practice providers, as well as permitted TM/TH services and treat- ments, in conformity with state regulations, organizational policies, patient population needs, and available human and technical resources.

Follow-up. Prepare protocols addressing communication and follow-up requirements with supervising physicians, if relevant.

Telehealth training. Educate advanced practice providers and other authorized clinicians on the proper use of telehealth tech- nology. If possible, schedule mock patient visits to ensure that practitioners are comfortable with TM/TH tools and procedures, and utilize practice modules focusing on how to properly respond to equipment and software glitches.

Patient selection. Not every patient is a suitable candidate for remote care. Adopt formal selection criteria, taking into consider-ation medical factors as well as Internet access and computer skills.

Patient verification. Confirm patient identity prior to TM/TH encounters, in order to prevent identity theft and fraudulent insurance billing.

Patient disclosure. Inform patients in writing when a nurse practitioner or other approved non-physician provider is delivering TM/TH services, including the signature of the practitioner and his or her licensing/certification designation.

Patient privacy. Remember that HIPAA requirements remain intact and are as applicable to TM/TH consultations as they are to in-person visits. Using two-way video interface platforms and other related communication applications, ensure that authorized providers receive adequate, documented training on how to securely share information with remote sites.

Documentation. Document virtual care delivery in the patient’s healthcare information record in accordance with the organization’s standards for in-person care. In general, virtual care notations should include patient history, review of systems, information used to make treatment decisions, follow-up instructions, referrals to specialists and discussions with supervising physicians, if necessary. All patient-related electronic communications should be included in the patient healthcare information record. In addition, note that the service was provided through interactive telecommunications technology, indicating the location of the patient and the provider, as well as the names and roles of other persons participating in the virtual event.

Audit TM/TH care. Following remotely held sessions, share care-related information – including adverse events and any complaints received about any of the providers – between the originating and distant site.

Address potential HIPAA exposures associated with digital communication platforms.

At one time, FaceTime, Zoom, Skype and other consumer-based video communication platforms were not extensively used in the healthcare context due to security and privacy concerns, especially regarding their data encryption limitations and the potential for third-party eavesdropping. Recently, however, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has authorized their use – as well as messaging applications such as WhatsApp and Viber – in order to facilitate provider-patient contact during the pandemic. The agency is also

exercising discretion pertaining to enforcement of HIPAA privacy laws, stating that providers who utilize these digital tools in good faith will not be penalized for noncompliance.

The extent to which hospitals and other healthcare organizations will continue to employ these technologies once the federal enforcement discretion is lifted remains unclear. Their continued usage may depend upon the platforms’ ability to safeguard data and protect patient confidentiality. The following actions, among others, can significantly enhance privacy during video conferencing and minimize the potential for security breaches:

- Implement technical safeguards to protect electronic health information, including password-protected access to software applications, end-to-end encrypted data transmission, formal procedures for obtaining patient information during emergency consultations and automatic log-off times.

- Draft a medical staff protocol to ensure that only trusted, authorized providers are granted privileges to engage with patients through video conferencing technologies.

- Verify that telecommunication platforms can interface with desktop computers and audiovisual equipment, as well as connect with tablets, smartphones and other handheld devices.

- Select products offering encrypted chat features, so that multiple parties can safely participate in conferences.

- Ensure that video conference hosts can maintain full control of meetings by limiting participation and expelling unauthorized attendees.

- Create effective privacy features for conferencing, including password-protected access to chat rooms, passcodes for digital waiting rooms and locked room protections.

- Routinely test privacy control features, such as mute/unmute settings for participants and locks that restrict screen sharing.

- Establish a security protocol for providers who work from home, Internet cafes or other remote locations, and ensure that the protocol is aligned with HIPAA privacy requirements. (See “Tips for Video Conferencing from the Homes of Providers,”)

Healthcare organizations that currently use consumer video conferencing applications are encouraged to migrate to a health- care-specific, HIPAA-compliant platform designed to accommodate their unique needs. In addition, organizations may need to enhance their technical and administrative cybersecurity infrastructure to help combat security threats associated with increased online traffic.

Tips for Video Conferencing from the Homes of Providers

- Update the organization’s virtual private network (VPN) with software patches and security configurations, in order to ensure safe transmission of data from providers’ home networks through the VPN.

- Monitor and test the limits of the VPN in anticipation of increased network traffic, and make adjustments for pro- viders who require increased bandwidth.

- Require that users provide authentication before logging onto the VPN, and educate providers about the risk of “phishing” attempts – i.e., fraudulent efforts to per- suade users to reveal personal information for purposes of identity theft – by computer hackers.

- Guard against computer viruses and other malware by installing effective security software on all devices connected to the VPN.

- Ask providers to designate themselves as sole system administrator on their personal home network and to change their network router password frequently.

- Direct providers to select a new password for each video conference and refrain from disclosing private infor-mation about the conference subject in meeting notices.

- Advise providers to store all patient care data on a secure laptop or other device that is separate from their main home computer system.

- Strictly prohibit sharing of sensitive files during virtual meetings, instead utilizing secure file-sharing technologies for this task.

Conduct due diligence regarding vendors.

There are many vendors of TM/TH products and services, and selecting the safest and most suitable tools requires careful consid- eration of multiple factors, including system capabilities, technical specifications, compatibility with existing digital infrastructure, privacy features and post-sale service.

After performing preliminary product and vendor research, submit a formal Request for Information (RFI). RFIs should request a range of information from vendors, including the following:

- The vendor’s profile (e.g., ownership arrangement, size of workforce, domicile, years in business).

- Total money allocated to research and development, a sign of commitment to quality and innovation.

- Proof of product compliance with HIPAA requirements, such as HITRUST Alliance certification or a similar vetting.

- Presence of certified trainers specializing in healthcare applications.

- Names of comparable healthcare clients who can provide references.

- Extent of the product’s mobile compatibility, permitting providers to access information through their smartphones or other handheld devices.

- Availability of on-site and web-based training, as well as 24/7 customer support.

- Software licensing arrangements and associated user fees.

- Means of documenting patient interactions when using the product or service.

- Implementation costs, including hardware and software requirements, staff training, program maintenance and upgrades, and patient education on use of web-based portals.

When acquiring digital applications from a vendor, a user license is generally considered preferable to a subscription arrangement. By purchasing a software license, organizations obtain ownership of the product and exercise full control of the data. By contrast, a subscription often involves centralized data storage by the vendor, which could potentially lead to third-party interference. In either case, request that vendors sign a Business Associate Agreement to ensure they remain legally accountable for HIPAA privacy and security regulations. Consult with legal counsel regarding con- tractual arrangements with vendors and applicable conditions and provisions.

For a variety of reasons – including evolving technology, mounting economic pressures and the lingering impact of the COVID-19 pandemic – telemedicine/telehealth utilization has expanded considerably in recent years. While promising increased patient access and safety, virtual care also presents significant liability and compliance exposures. By remaining cognizant of changing regulations, and implementing sound protocols in such basic areas as provider licensure and training, verification of patient identity, service documentation and vendor selection, healthcare organi-zations can minimize the risks associated with remote care while maximizing the efficiency and convenience of this innovative healthcare delivery mode.

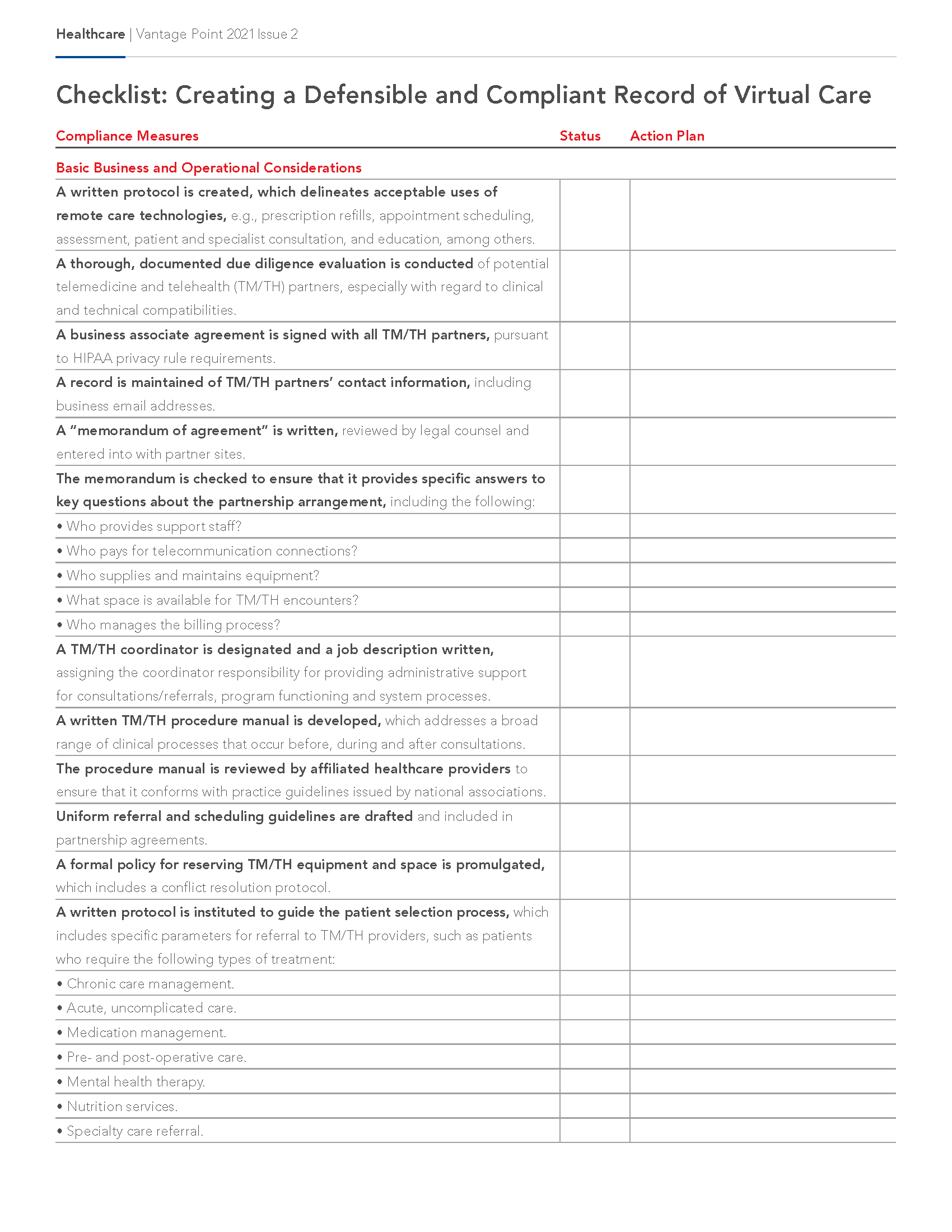

Below is a portion of the Creating a Defensible and Compliant Record of Virtual Care checklist. Click the image or the link below to download the full checklist.

Checklist: Creating a Defensible and Compliant Record of Virtual Care

Checklist: Creating a Defensible and Compliant Record of Virtual Care

This resource serves as a reference for healthcare organizations seeking to evaluate risk exposures associated with telemedicine and telehealth. The content is not intended to represent a comprehensive listing of all actions needed to address the subject matter, but rather is a means of initiating internal discussion and self-examination. Your organization and risks may be different from those addressed herein, and you may wish to modify the activities and questions noted herein to suit your individual organizational practice and patient needs. The information contained herein is not intended to establish any standard of care, or address the circumstances of any specific healthcare organization. It is not intended to serve as legal advice appropriate for any particular factual situations, or to provide an acknowledgement that any given factual situation is covered under any CNA insurance policy. The material presented is not intended to constitute a binding contract. These statements do not constitute a risk management directive from CNA. No organization or individual should act upon this information without appropriate professional advice, including advice of legal counsel, given after a thorough examination of the individual situation, encompassing a review of relevant facts, laws and regulations. CNA assumes no responsibility for the consequences of the use or nonuse of this information.

Editorial Board Members

Kelly J. Taylor, RN, JD, Chair

Janna Bennett, CPHRM

Peter S. Bressoud, CPCU, RPLU, ARe

Lauran L. Cutler, RN, BSN, CPHRM

Hilary Lewis, JD, LLM

Lauren Motamedinia, J.D.

Katie Roberts

Publisher

Patricia Harmon, RN, MM, CPHRM

Editor

Hugh Iglarsh, MA

Published by CNA. For additional information, please contact CNA at 1-866-262-0540. The information, examples and suggestions presented in this material have been developed from sources believed to be reliable, but they should not be construed as legal or other professional advice. CNA accepts no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of this material and recommends the consultation with competent legal counsel and/or other professional advisors before applying this material in any particular factual situation. This material is for illustrative purposes and is not intended to constitute a contract. Please remember that only the relevant insurance policy can provide the actual terms, coverages, amounts, conditions and exclusions for an insured. All products and services may not be available in all states and may be subject to change without notice. “CNA” is a service mark registered by CNA Financial Corporation with the United States Patent and Trademark Office. Certain CNA Financial Corporation subsidiaries use the “CNA” service mark in connection with insurance underwriting and claims activities. Copyright © 2021 CNA. All rights reserved. Published 7/21. CNA VP21-2.

Nurses Service Organization and Healthcare Providers Service Organization are registered trade names of Affinity Insurance Services, Inc.; (TX 13695); (AR 100106022); in CA, MN, AIS Affinity Insurance Agency, Inc. (CA 0795465); in OK, AIS Affinity Insurance Services, Inc.; in CA, Aon Affinity Insurance Services, Inc., (CA 0G94493), Aon Direct Insurance Administrators and Berkely Insurance Agency and in NY, AIS Affinity Insurance Agency.